You Don't Need the DOM Ready Event

It usually takes a long time for the DOM ready event to fire. During this time, many parts of a webpage are inactive as they wait for Javascript to kick in and initialize them. This delay is significant and makes a rich web application become available slower. Creates a bad user experience, doesn’t adhere to any design pattern and is, really, not needed…

Why wait for the DOM Ready Event?

First of, when I am talking about the DOM ready event, this includes any other kind of readyish events that are fired by the browsers. window.onload, readystateChange, jQuery ready event and all other variants.

So, it is very common today for Javascript applications to wait for the DOM ready event before they start executing their payload. The reasoning behind this is to have a fully rendered and ready to go DOM object.

As per jQuery’s documentation:

The handler passed to .ready() is guaranteed to be executed after the DOM is ready, so this is usually the best place to attach all other event handlers and run other jQuery code.

Why you don’t need the DOM Ready Event

It all boils down to the order of elements positioning in the final document that is published and served by a webserver. Understanding the importance of this fact enables web applications to load faster and provide the fastest possible UX.

Relying on DOM Ready also implies that the script elements are in the document HEAD. As per the HTTP/1.1 spec browsers can download no more than two components in parallel per hostname. Thus, we use CDNs or generally multiple hostnames for our static content. However when a script is loading, the browser will not start any other downloads, even on different hostnames!

Order Matters!

There is no reason at all to have any script tags in the HEAD. Not even at the top of the BODY tag. Scripts’ position is at the bottom of the document, right before the closing of the BODY tag. An exception are scripts that need to perform a document.write, like ads scripts. Pretty much everything else can easily be moved to the bottom.

All script elements are immediately invoked. So if they are positioned at the end of the document, when they are invoked the document has already been parsed, rendered and all the nodes exist in the document. Therefore they are immediately accessible to the javascript application.

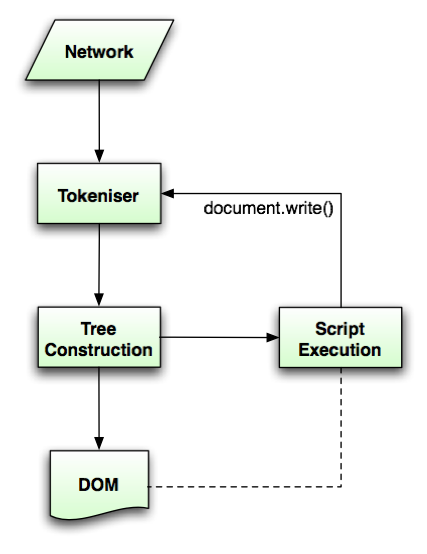

The following illustration is from the overview of the parsing model at w3c:

Tokens are handled by the “Tokeniser”, they are each element that is being parsed from the text document. The reason why the DOM rendering process is reentrant is because of the document.write() and other DOM manipulation methods a script can possibly execute.

Which in code means that:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

<span id="spanOne"></span>

<script>

var one = document.getElementById('spanOne');

var two = document.getElementById('spanTwo');

// span one was defined before the script so it's available and can be manipulated

one.innerHTML = 'Gangnam';

// span two is defined after the script and is undefined

try {

two.innerHTML = ' Style';

} catch(e) {

console.log('Error, span two not defined', e);

}

</script>

<span id="spanTwo"></span>

A more complete example

Consider this sample document:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head lang="en">

<script type="text/javascript" src="initLoggers.js"></script>

</head>

<body>

<div id="main-content"></div>

<div id="logger"></div>

<script type="text/javascript">

log('Inline JS at bottom of BODY. Loading jQuery...');

</script>

<script src="//ajax.googleapis.com/ajax/libs/jquery/1.8.3/jquery.min.js"></script>

<script type="text/javascript" src="ourApplication.js"></script>

</body>

</html>

The first script loaded at line 4 initLoggers.js defines some helper functions for measuring the time that events occur since the page starts loading. We include this file in the HEAD to illustrate the flow of execution and the time differences of the process.

This is the initLoggers.js script:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

// get the current time difference between page

// load and when this func was invoked

function getTimeDiff() {

return new Date().getTime() - performance.timing.navigationStart;

}

var $log, jqLoaded = false;

function log(message) {

if (jqLoaded) {

$log = $log || $('#logger');

$log.append('<p><b>' + getTimeDiff() + '</b>ms :: ' + message);

}

if (window.console) {

console.log(getTimeDiff() + 'ms :: ' + message);

if (console.timeStamp){

console.timeStamp(message);

}

}

}

log('On HEAD, starting...');

Notice on line 4 the use of performance, a pretty useful debugging object. Try it in your console and see the available methods and properties of navigation timing available at your browser.

So after jQuery loads, the main application script ourApplication.js is loaded:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

log('jQuery loaded.');

jqLoaded = true;

$(document).ready(function(){

log('DOM Ready fired');

$('#main-content').append('Style!');

});

log('Inline JS appending content...', true);

$('#main-content').append('Gangnam ');

As we mentioned, script elements are blocking until they load, and when they do they immediately execute. Line 11 performs an inline DOM manipulation. As expected, the manipulation will happen right there, synchronously. Soon after, DOM Ready event fires and executes the payload in lines 6 and 7.

When this page runs, this is what we see in the console:

1017ms :: On HEAD, starting...

1025ms :: Inline JS at bottom of BODY. Loading jQuery...

1083ms :: jQuery loaded.

1086ms :: Inline JS appending content...

1099ms :: DOM Ready fired

The difference of 13ms between inline JS and DOM Ready execution may not look as much, but keep in mind this is an empty page. Running similar timing scripts in a moderately loaded document in development state yields these results:

290ms :: On HEAD, starting...

478ms :: Stylesheets loaded

488ms :: Inline at bottom of BODY, start loading jQuery...

587ms :: jQuery loaded, creating on DOM.Ready listener...

602ms :: First bootstrap JS file loaded, our UI can start

1525ms :: All inline scripts finished loading.

1538ms :: DOM Ready fired

The page was loaded from localhost, so time is faster on HEAD. Because the page is in development state, all assets are loaded individually in the document, meaning multiple style and javascript files are requested from the server.

In this case you can see the significant difference between when the first inline javascript file was evaluated and invoked (602ms) and when DOM Ready finally fired (1,538ms).

Faster page rendering, faster time when page becomes usable, faster page loading, better user experience. It’s time to let go of the DOM Ready Event.

Have some fun with this plnkr where you can find the code for the examples used in this post.

blog comments powered by Disqus